We continue our look at some of the main sites that we see as we descend the Mount of Olives on the “Palm Sunday” walk. This special walk is always a highlight of our time in Jerusalem, and there is much to see. Pilgrims who follow this path often enjoy the opportunity to linger for some spiritual reflection time at the Pater Noster Church. The Latin name literally means the “Our Father” Church, so labeled because tradition associates the site with the place where Jesus taught the disciples the Lord’s Prayer.

Documentation from the third century refers to a cave on the Mount of Olives where Jesus taught his disciples. Subsequent visitors believed that the small grotto on the grounds of what is now the Pater Noster Church was that very cave. In Christ’s time, a cave in that area would have been a secluded place for him to meet with the small group of disciples.

However, the first church built on the site was not associated directly with that tradition. The original church was called Eleona (Greek for “olive grove”), and it was built by Emperor Constantine’s mother Helena in the early fourth century to mark the place of Jesus’ ascension to heaven. Within a century, Christians were remembering the ascension at another location nearby, higher up on the peak of the ridge. That is where the Chapel of the Ascension is located, and I will talk about that on the blog next week. The Persians destroyed the Eleona Church in 614.

During Crusader times in the twelfth century, Christians again focused on the cave as a place where Jesus taught the disciples. This time, the specific connection with teaching the Lord’s Prayer was emphasized, and the Crusaders built a chapel there. Most of the current Pater Noster Church was completed as a Carmelite convent church, along with the cloister, in 1874. The cave and the original foundations of the fourth-century Byzantine church were rediscovered in 1910, and a reconstruction of that church was begun in 1915 until it was halted in the 1920s. The partially reconstructed Eleona Church is visible, along with the cave, and the nineteenth-century Carmelite church.

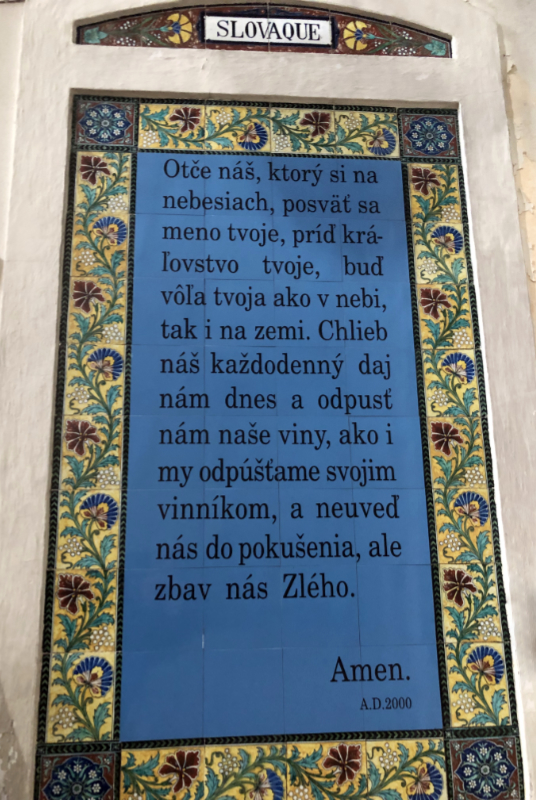

Christian pilgrims from the Crusader era also wrote about seeing the Lord’s Prayer inscribed on marble plaques in Hebrew and Greek. Today the cloister contains colorful ceramic plaques throughout, each of which presents the Lord’s prayer in a different language of the world. How many? Currently, 140! This is perhaps one of the most striking features of the site for pilgrims, and it is meaningful to view and appreciate the faith we share with others around the world and to find the prayer in one’s own language among the many others.

The cave is in the courtyard of the church, and visitors can enter it. Most groups take the opportunity to pray the Lord’s Prayer together and to reflect on Jesus’ words while inside. The church building and the rest of the grounds are a peaceful place to wander in continued meditation on the Lord’s teaching.

On our January 2022 pilgrimage, we were able to record our amazing tour guide George reading the prayer in Aramaic—the original language in which Jesus would have taught his disciples. You can see that clip in my post, The Lord’s Prayer in Jesus’ Language.

Featured Image “Église du Pater Noster” by Etienne Valois is licensed under CC BY-NC-ND 2.0.

Image “Pater Noster Church – exterior” by Larry Koester is licensed under CC BY 2.0.