In my last post (Healing Pools, part 1), we began a look at two significant locations of healing miracles in the Gospel of John: the Pool of Bethesda and the Pool of Siloam. Jesus performed remarkable wonders of healing for individuals at each place, which John records in chapters 5 and 9, respectively. We continue here with more on the Pool of Bethesda.

In John 5, near the Pool of Bethesda, Jesus encountered a man who had been an invalid for 38 years. In Jesus’ time, the pool was outside Jerusalem’s city wall, and the nearest gate was the “Sheep Gate” (hence the detail that John gives in 5:2). We are told that at this pool, “a great number of disabled people used to lie—the blind, the lame, the paralyzed” (5:3). Some ancient manuscripts expand at this point and point us to a popular tradition associated with the pool: “They waited for the moving of the waters. From time to time an angel of the Lord would come down and stir up the waters. The first one into the pool after each such disturbance would be cured of whatever disease they had.” This sheds light on what the man means when he says, “I have no one to help me into the pool when the water is stirred. While I am trying to get in, someone else goes down ahead of me” (5:7).

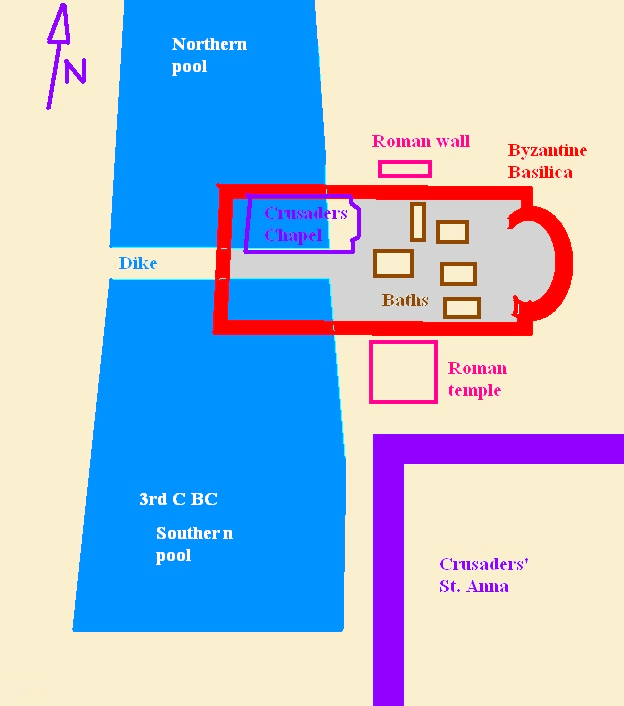

In addition to parts of the main pool, archaeologists have excavated an adjacent Roman-built bath complex probably dating from the first century. This included an asclepion, that is, a healing temple sacred to the Greek god of medicine and healing, Asclepius. The baths were a part of healing rituals, and they were most likely where the sick and lame congregated. The larger, main northern and southern pools were much too deep for those with physical challenges serious enough for them to be there in the first place. If this is the case, then it might give us insight into why Jesus both asks the man if he wants to get well (5:6) and later tells him at the Temple to stop sinning (5:14). Could it be that Jesus takes issue with the fact that the man had chosen to seek healing at a place dedicated to a Greek and Roman god whom he believed to be his hope for healing?

The man whom Jesus healed at the Pool of Bethesda on that occasion was not guilty of sin in “taking up his mat” on the Sabbath, as the Jewish leaders accused him (5:10). While we don’t know for certain, knowledge of the site and its history perhaps helps us to see that this man was guilty of trusting in false gods rather than in the One who knew his name, cared for him deeply, and was the one and only source of the mercy he sought. Indeed, the prophet Jeremiah had spoken God’s objection over Israel centuries before: “My people have committed two sins: They have forsaken me, the spring of living water, and have dug their own cisterns, broken cisterns that cannot hold water” (2:13).

Thirty-eight years is a long time, but at the end of that wait, it was not Asclepius who found him and healed him. It was Jesus, the one whom John makes clear is the true source of “living water.”